The luminous face of Vera Karalli.

For me, Yevgeni Bauer is one of the cinematic greats of the teens, and indeed of silent cinema in general. In a word, his films are elegant. Always beautifully composed in terms of framing, editing, and mise-en-scène, most of his films that I’ve seen are society dramas with a strong psychological dimension and often a gothic sense to them. His most frequent collaborators were actresses Vera Kholnodnaya, so loved that when she died in 1917 Russia declared a national day of mourning; actress and ballerina Vera Karalli; and cinematographer Boris Zavelev (who later shot Zvenyhora); of course, he also worked with many other leading actors and personnages of the day.

После Смерти (After Death; translit. Posle Smerti), starring Vera Karalli and Vitold Polonsky in the lead roles, was released a few days after Christmas in 1915. It tells the story of Andrei Bagrov, a scholar living in relative seclusion to the world.

Andrei does have one friend, Tsenin, who persuades him to come to a party with him. Andrei is ill-at-ease, but allows Tsenin to sweep him along.

It’s there that Andrei meets Zoya Kadmina. He only meets her briefly and indeed walks away almost straight away, but he is struck by her large dark eyes. Zoya Kadmina seems equally captivated; we see her gaze thoughtfully, almost assessingly, after him.

Some time later, Andrei goes to see her sing:

Yet even then, he refuses Tsenin’s offer to make a formal introduction. He is, after all, a mama’s boy living the life of the mind. It’s at the end of this scene where the famous close-up shot of Karalli’s face appears.

She’s wonderful.

Afterwards, we see Zoya writing a note. When Andrei receives it, he throws it in the bin … then retrieves it. With misgivings, he decides to go and meet Zoya in Petrovskiy Park. But their meeting is cryptic and unfulfilling, and both parties leave perplexed. It’s three months later when he learns from the newspaper of her suicide, rumoured to be due to unrequited love. After this he starts to be haunted by her, in dreams and visions.

The rest of the story concerns Andrei’s grasp on reality loosening, in parallel with his search for answers; he visits her family and is told about her death (this allows it to be shown in flashback, in all its full, operatic glory); he acquires her diary; he continues to be visited by her in dreams and apparitions. Since this is a Russian film, one can guess how it ends: with perfectly aesthetic gloominess.

Bauer, master stylist

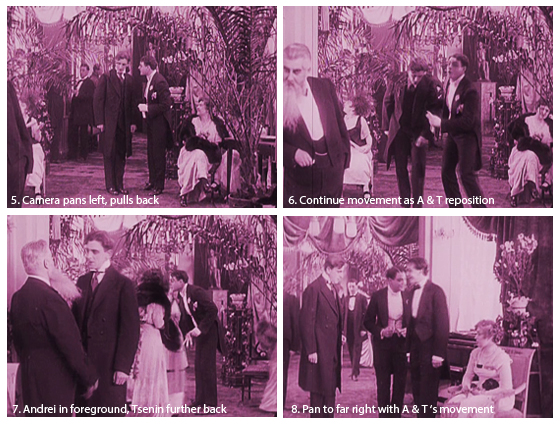

It’s not a flawless film; as a contemporary commentator in Obozrenie Teatrov (Theatre Review; quoted in the indispensable anthology Silent Witnesses) remarked, the scenes of the visions do become slightly repetitive. But when the film is so stylish, does it really matter? Bauer’s command of film form is outstanding and so much more creative than many other films of the era. The scene with Andrei and Tsenin arriving at the party, in particular, is a masterclass of direction, and the kind of work that would be an Oscar-showreel shot even today. Although in After Death (and elsewhere) Bauer generally uses conventional editing techniques, the party scene, which lasts a full three minutes unbroken, is a highly refined upgrade of the tableau styling of staging/direction which was used to great effect before the rise of montage. However, tableau would be a misdescription here, because the camera is anything but static – it’s almost constantly in motion, zigzagging throughout the space. Opening with Andrei and Tsenin in the background of the shot, the camera follows them as they weave around the salon, interacting with different people and activating different parts of the frame and set. Not only does this set the scene and establish a mood, but it also reinforces the characterization (Andrei’s hesitancy, Tsenin’s gregariousness). It’s a virtuosic example of visual storytelling without recourse to editing. Rather than describing it in words, I broke down the shot in a series of images:

Please forgive the errors in terminology, I didn’t keep the PSDs so now I can’t easily edit the text.

Aside from this, there are a wide variety of framings, and After Death (and Bauer’s work in general) features some of the most accomplished staging and lighting of the teens. And consider the composition of a shot like this, our introduction to Andrei:

Another example of visually striking technique that also has something to say about characterization.

Considering Zoya and Andrei

Although the story is really that of a simple melodrama, albeit a dark one, I find some aspects of it enigmatic. The story quite clearly positions Andrei as a strange, obsessive man, unconsciously warped by his lack of exposure to society and his possible (probable?) Oedipal issues. Yet it is not entirely a one-sided obsession; Zoya Kadmina is also drawn to Andrei, and pursues him to some extent; though this is tempered by her apparent rejection at their meeting: “Why speak like this? Oh, I am mad! I was mistaken about you, your face …” To me, this implies that Andrei was not the one of which she dreamed (in her diary: “HE is to decide my fate”); or in a wider sense, that Zoya’s suicide was not really due to love (or lack of it), but rather other psychic disturbances.

Here in After Death, Zoya appears in life in three scenes, but for the rest of the story she is quite literally a wraith, a projection of Andrei’s heart and mind. One of my close friends is currently preparing a thesis on Yevgeni Bauer’s films, and we were recently discussing how though his female characters are in many ways progressive, they are also often characterized as fragile. Quite often they are literally sensorially deficient in some way (e.g., Lily is blind in The Happiness of Eternal Night, 1915; the dancer Gizella is mute in The Dying Swan, 1917) or they are physically at risk (e.g. The Twilight of a Woman’s Soul, 1913); or as here, the subject of obsession (Daydreams, 1915). This framing of women as delicate, poetically flawed creatures certainly neutralizes them as sexual threats. Without wanting to oversell the idea, it is almost as though there is an equation balancing physical integrity and independence/emotional strength; fortitude through suffering? (Admittedly this doesn’t apply so strongly to After Death, more to other films). It’s interesting to speculate about how this kind of characterization might be linked to dominant ideas about womanhood in upper-class society in the pre-Revolutionary era, or Russian cultural narratives in general, but I’m not knowledgeable enough to draw a conclusion. In any case, it’s rather different to the ideal of women in the Soviet era: healthy, comradely, accorded (theoretically) a status of equality via a rhetoric of equivalence rather than difference. (Though it must be said that many Soviet silents, particularly the canonical ones, are quite male-centric; but when you scratch the surface, you find excellent, highly intriguing films like Bed and Sofa, 1927).

Bauer v. Turgenev

After Death is based on the Ivan Turgenev short story Klara Milich (Клара Милич; 1882). I’ve been reading a bunch of Russian literature lately (in wintertime, it seems appropriate), and I sought out a copy of the Turgenev story, thinking that it would be interesting to compare with Bauer’s adaptation.

The plot of the film is broadly similar to that of the film, though all of the names are different. In Turgenev, Andrei is called Yakov Aratov; Tsenin is Kupfer, a Russified German; and Zoya Kadmina is of course Klara Milich. The name change from Milich explicitly references Evlaliya Kadmina, the inspiration for Turgenev’s story; the real Kadmina was a nineteenth-century actress who took poison on stage as the result of an unhappy love affair, dying a few days later.

Evlaliya Kadmina. [Photo source]

A detail of the story I found particularly interesting was the way that Yakov obsessively looks at Klara’s photograph through a stereoscope, creating the illusion of three-dimensional life. Although Bauer shows Yakov tinkering with photographic apparatus and the photograph, the idea of the stereoscope wasn’t brought across, although Bauer gives the general sense of Yakov/Andrei’s obsession with the photograph.

Yakov thinks often of Klara, with the kind of introspection which can’t easily be rendered on film. His ambivalence towards her leads him to consider her at times very appealing despite not being a classical beauty, and at other times objectionable, e.g.: “She was certainly bad, unbalanced. ‘A gipsy!’ (Aratov could not think of a worse description)” . Interestingly, in the story Yakov is already somewhat primed to think of Klara as off-kilter. He is surprised when he learns her (uncommon?) name, because it reminds him of a poem he had read, based on the character Clara Mobray from Sir Walter Scott’s St. Ronan’s Well (1823), featuring the line “Unhappy Clara! Poor crazy Clara!”, a refrain which is repeated several times in Turgenev’s story. Although Yakov had seen Klara briefly at the party Kupfer dragged him to, they were not introduced there as in the film, and it is only when Yakov sees her perform that he remembers that he had seen her at the party – “and he had not only seen her but had even noticed that she had several times looked at him with her dark, intent eyes, with particular persistence”.

Turgenev’s short story offers little more clarity of Klara’s thoughts and motives than does the film. As with Zoya, we only see Klara secondhand, although the reader gains more insight into her temperament through the conversation that Yakov has with Klara’s sister Anna. Klara was passionate, unhappy, and fatalistic, believing that events on the day of her performance at the soirée would decide her fate. But why Yakov, and was it destiny or random chance? And did she kill herself simply because she could no longer bear to live (as Yakov initially believes, after talking to Kupfer), or because of Yakov’s rejection of her (as he comes to believe)? To the audience these questions remain open. In an essay called “Her Final Debut: The Kadmina Legend in Russian Literature”, Slavic scholar Julie A. Buckler points out that the fragmented nature of Milich’s character may be an intentional challenge to the audience:

The figure of Klara Milich exists in Turgenev’s story as a reconstruction and a recollection, as an interpretation of first-person romance texts, an indistinct figure in a black veil [at their meeting on the boulevard], a character acted out by others [Anna], a photograph, a diary, an unsigned note, an unwritten biography [Yakov’s pretext for visiting her family], as gossip, and finally, as an image contructed by Aratov’s own unreliable perceptions and dream-visions. Does the story succeed in its attempt to construct a character and reconstruct the story of her demise? Or is its purpose to show us how hard we try to do this?

There are other minor differences between the film and the story: for example, the character of the Georgian princess is cut from the film; the details of Klara’s flamboyant death are revealed by Kupfer, not Anna. His first night vision features him first following a woman across a steppe before sinking back into an entrapping tombstone, after which Klara appears and tells him, “If you want to know who I am, go there!” In the film Zoya does not similarly exhort him, nor is the scene played exactly the same way (a sensible choice by Bauer, since the introduction of a random woman in the vision would probably have been confusing). In both cases, Andrei/Yakov is spurred to visit Kazan (in modern-day Tatarstan) to call upon Zoya/Klara’s family.

As his visions increase, Yakov falls further into delusion and/or love, reaching a state of ecstasy that is not really depicted in the film. In Yakov’s pre-death delirium, he tells his aunt, “But what are you crying for, Auntie? Because I have to die? But don’t you know that love is stronger than death? Death! Death, where is thy sting? You should not weep, but rejoice, the same as I rejoice.” In a description that reminded me slightly of the ending of All Quiet on the Western Front, Yakov dies with a serene smile on his face.

In 1916 the art journal Pegasus published correspondence between Bauer and a commentator (“Mme N.I.”) who critiqued his choices in adaptation. Interestingly, she touches on the ideas about feminine fragility I mentioned above when she asks: “Why depict the small spindly figure of Zoya Kadmina instead of the full-grown beauty Klara?” I object to the rather derogatory description of Karalli, because I think she’s brilliant, but it’s an interesting point. N.I. also wondered why all of the names were changed, and why Andrei was depicted as more stylish than sickly. Bauer responded with a polite plea to artistic license:

I totally agree with Mme N.I., and we think that her observations are applicable to all pictures illustrating Turgenev’s works. It is our view that the cinema has still not found the movements and pace required to embody Turgenev’s delicate poetry. Nor alas, will it find them soon, since film directors have been educated in conditions allowing them to take barbarous liberties with the authors. Since, in the initial phase of their career, they are involved merely with works that are hopeless from the literary point of view, they grow accustomed to doing as they wish, to altering arbitrarily the intentions, the situations and even the heroes invented by the author. Turgenev should be approached in a different spirit and with different habits.

In summary

An excellent, thought-provoking work from one of the best-kept secrets of cinema history; Bauer’s death from pneumonia in 1917 was a huge loss to the Russian cinema, and film art in general.

— — —

После Смерти (After Death). Dir. Евгений Бауэр (Yevgeni Bauer). Russian Empire: Khanzhonkov, 1915.

After Death is preserved by Gosfilmofond (the State Film Fund of the Russian Federation). It was released on DVD with a really nice score by the BFI (UK) and Milestone Films (US).

A super post on one of my favourite films and one of my favourite directors from the period! Paul

LikeLike

Thank you! Bauer is just wonderful.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on ithankyouarthur.

LikeLike

Another terrific film starring Vera Karalli 🌸 with Vitold Polonsky ⭐️! The cinematography is superb along with a first rate plot! I also enjoyed Karalli and Polonsky in The Dying Swan (1917) which I’ve watched multiple times as I’m a huge fan of both film stars. Thank You as always for your first rate blogs with GIF’s which I enjoy sharing with my fellow fans of silent films that aren’t as well known.

LikeLike

Thank you so much! I obviously adore this film (and The Dying Swan, of course).

LikeLiked by 1 person

Vitold Polonsky reminds me a bit of British actor James Norton. Vera Karalli 🌺 had those amazingly expressive dark eyes! I recently learned of another Vera Karalli film called Nabat (The Alarm-1917) Which was shown at a screening at the Museum of Modern Art about 20 years ago with other Russian silents. I would love to watch that one too someday!

LikeLike

Oh yeah, I would too. I’ve been aware that Nabat survives, but I’ve never managed to get hold of a copy. I hope one becomes available someday! 🤞

LikeLiked by 1 person