Six weeks after the fact, you say? From the Department of Better Late than Never comes my recap of Il cinema ritrovato 2018: a wonderful festival of archival film of all eras and countries. Spoiler alert: I had a blast!

Sunday was my first day of film-viewing, and the highlight of the day may just have been Mary Pickford-Ernst Lubitsch collaboration Rosita (USA 1923), screened under the stars in the Piazza Maggiore. Due to the film’s relative unavailability and the fact that Pickford famously denounced it—to the extent of overtly discouraging its preservation—interest was high. Would Pickford’s high-spirited hoyden type be a match for Lubitsch, transitioning from the earthy humour of his German films to the high-society sophistication of the Lubitsch Touch? I enjoyed Rosita, but was left thinking that these two huge creative forces never quite harmonised. Rosita was made the same year as Pola Negri vehicle The Spanish Dancer: the two films have essentially the same story, both being adaptations of the opera Don César de Bazan. I’d also rate The Spanish Dancer as ‘good but not great’—it’s interesting to think about what each film might have looked like with a switch of stars (or directors).

Rosita includes some great Lubitschian moments, such as the perfectly staged and edited scene where Rosita sneaks morsels from the royal fruit bowl as she flits back and forth across the room. Though it’s absolutely Pickford’s film, Rosita benefits from a good supporting cast: the always excellent Irene Rich shows up as the Queen; Holbrook Blinn commits to the role of the slimy King; and as Pickford’s love interest Don Diego, George Walsh knows his place and mostly hangs around smouldering appropriately.

Strangely enough, Rosita was preceded by René Clair’s Entr’acte (FR 1924), the Dada film scored by Erik Satie. This programming worked to my advantage, as this avant-garde classic scared off a few film-watchers, freeing up some seats for me and my friends!

More Lubitsch (and can one ever have enough?) was on offer earlier in the day with the existing fragment of Der Fall Rosentopf (The Rosentopf Case, DE 1918), one of the ‘Sally’ series of films in which Lubitsch stars as the titular Jewish Berlinese man-about-town. Lubitsch plays it broadly, and as always, he is great fun to watch. The same screening programme included Gräfin Küchenfee (Countess Kitchenmaid, DE 1918), starring Henny Porten as both the dissolute and vulgar Countess Gyllenhand and the kitchenmaid Karoline, a wannabe actress who ends up impersonating the Countess. Though nowadays not enjoying the reputation of some of her contemporaries, Porten was one of the most successful and beloved actresses of the German silent screen; she would later establish her talkie career with Kohlhiesels Töchter (Kohlhiesel’s Daughters, DE 1930), another dual role.

I’ve never ‘got’ Henny Porten before—she’s seemed pretty staid to me in other films. But with a film like Gräfin Küchenfee, one can well understand her popularity. Porten is playing both roles to the hilt and clearly having a ball, and the result is very charming indeed.

Another notable German silent was Christian Wahnschaffe (DE 1920), directed by Urban Gad, aka the former Mr. Asta Nielsen. I only caught Weltbrand (World in Flames), the first installment of this two-parter. Conrad Veidt plays an industrialist playboy who swans around emoting in delicate kimonos, then renounces his bourgeois life after he falls in with a group of revolutionaries. However, the ‘Christian among the proletariat’ plot mainly occurs in the second part of the film (Die Flucht aus dem goldenen Kerker; Escape from the Golden Dungeon); Weltbrand focuses on Conny’s developing social conscience and his relationship with Eva Sorel, a Parisian dancer who is part of the Nihilist/anarchist movement. As the female lead Eva, I really liked Norwegian actress Lillebil Ibsen (also seen in Pan, NO 1922). Ibsen was primarily a dancer—and there’s a wonderful scene of her cutting a rug in Weltbrand—but she’s also very likeable as a screen presence. Christian Wahnschaffe shows a panorama of society, and tempers its moral message with a healthy dose of melodrama. Not one of my greatest hits, but nonetheless interesting to see.

To France! Rue de la Paix (1926) was a treat: a love triangle set in the Parisian fashion world. The plot was relatively boilerplate, but what dresses, darling! And who could forget the scene set in the orangutan-themed nightclub?

Following this jazz age merriment, we returned to 1918 with Louis Feuillade’s Vendémiaire. The title refers to the grape harvest, and wine cultivation is not just part of the plot, but a metaphor for La France herself. Vendémiaire takes place at the end of the first world war, but the news that the war is over has not yet diffused to the Castelviel estate, busy with the grape harvest. While weary soldiers head home, escaped German prisoners are attempting to pass themselves off as Belgian farmworkers. Several Feuillade regulars show up, including Judex himself, René Cresté, and Édouard Mathé (Philippe Guérande in Les Vampires). I only caught the first part of the serial, but friends assured me that the malicious Germans got their comeuppance, and harmony was restored at Castelviel.

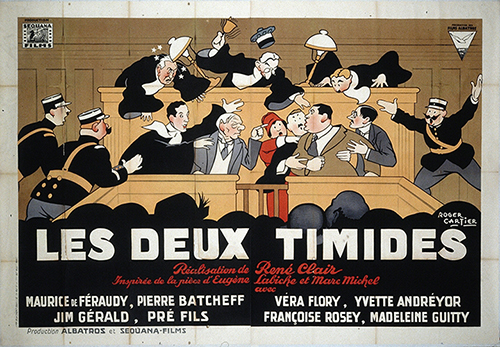

In terms of French film, the uncontested highlight for me was René Clair’s Les deux timides (The Two Timid Souls, 1928). It was simultaneously one of my best and most testing screenings of the festival, being so full that many people were turned away, on top of which (or because of which?) the air conditioning broke. Challenging, considering that we were in thirty-plus degree heat! However, the film itself was absolutely wonderful. Much like Un chapeau de paille d’Italie (An Italian Straw Hat, 1928), which I happened to have watched shortly before Il cinema ritrovato, Les deux timides is a refined comedy of manners, enacted with great grace and visual elegance. Absolutely one that I’ll be rewatching and recommending to my friends.

Another high point of the festival, certainly for me the most anticipated part, was the strand of Neapolitan programme devoted to the films of Elvira Notari. Probably the most notable figure in Neapolitan silent film, Notari wore many hats at her company Dora Film: director, producer, screenwriter, distributor, and more besides. I was familiar with Notari’s work via Guiliana Muscio’s wonderful book, Streetwalking on a Ruined Map: Cultural Theory and the City Films of Elvira Notari (1992), a true landmark of feminist film historiography, but I had not before had the chance to see any of Notari’s films. Despite her prolific output, only very few of Notari’s films survive, and they are not easy to see outside archives.

The Notari programme included È piccerella (1922) and ‘A Santanotte (1922), two of the passionate melodramas that were a specialty of by Dora Film. The two films, both based on popular Neapolitan songs, shared many cast members: Rosè Angione as the female protagonist, Alberto Danza as the lovesick male lead (both times named Tore), and Notari’s son Eduardo, who appeared in a large number of her films as a melancholic street urchin type, always called Gennariello. All of the Notari films were grounded in their setting of Naples, and specifically the life of the bassifondi (slum areas or the underworld; architecturally, the term basso refers to a ground-level apartment opening to the street, and therefore to society). Vivid in their intensity, and simultaneously fiercely realistic and spectacular in their emotionally explosivity: these were striking films. The scores were wonderful and added greatly to the viewing experience—I must especially note the projection of ‘A Santanotte, outdoors in the Cineteca courtyard, which was accompanied by the brilliant E Zézi Gruppo Operaio, a group dedicated to traditional Neapolitan music.

Image from the fragment compilation L’Italia s’è desta showing stencil colouring, which was the genesis of the Notari’s filmmaking business.

Also part of the Naples programme was Vedi Napule e po’ mori! (See Naples and Then Die!, 1924), one of a series of Naples-themed comedies that Leda Gys, Eugenio Perego, and Gustavo Lombardo made in the 1920s. Leda Gys is a joy, playing Pupatella, a sunny young woman who goes to America to become a film star, but just as much of a character is Naples herself: Vesuvius, the tarantella, the Feast of Piedigrotta.

Turning back time a little more, another section of Il cinema ritrovato was devoted to the golden age of Ambrosio, one of the most important film studios of the Italian silent era. This was especially interesting to me since I’m currently undertaking some related research—watch this space!—but also because of the excellence of the films themselves. La madre e la morte (The Mother and Death, 1911) stood out for its surrealist fairy-tale atmosphere, whereas Una partita a scacchi (A Game of Chess, 1912) saw Febo Mari locked in a game of chess with a madman. One of the biggest treats for me was finally seeing the 1912 version of Santarellina starring the great Gigetta Morano, which was a breezy delight from beginning to end.

Gigetta Morano and Mario Bonnard in Santarellina, an adaptation of the operetta Mam’zelle Nitouche (1883)

Being Turinese films, the selection also included several films starring Fernanda Negri Pouget, who regular readers will know is a particular favourite of mine. In La lampada della nonna (Grandma’s Lamp, 1913), she plays the title character as both a young woman and her older self, recountering the story of how she fell in love. Mary Cléo Tarlarini, another of Ambrosio’s leading actresses at the time, also featured in several films, such as the Dogaressa in Sogno di un tramonto d’autunno (Dream of an Autumn Sunset, 1911), who “annihilates and burns love itself”.

And finally, as a diva film fanatic, I would be amiss if I didn’t mention the screenings of Avarizia (Avarice, 1918), one of Francesca Bertini’s Sette peccati capitali (Seven Deadly Sins) series of 1918-19, and Lyda Borelli vehicle Carnevalesca (1918), which was wonderful to see again on the big screen. (I skipped La moglie di Claudio (The Wife of Claudius, 1918), having seen it before). I should also note that the festival saw the release of a diva film box-set, Dive! Lyda Borelli • Francesca Bertini. This means that at long last, Rapsodia Satanica is finally on DVD! True reason for celebration. However, the other three films in the box set (Ma l’amor mio non muore!, Sangue bleu, and Assunta Spina) are already available on DVD as single releases, making Dive! a slightly disappointing release for the hardcore fans.

Lastly! I want to give an honourable mention to the Georgian comedy Приданое Жужуны (Zhuzhuna’s Dowry, GSSR 1934; KA: ჟუჟუნას მზითევი), which was my last silent film viewing at Il cinema ritrovato 2018. As is well-known, sound technology permeated the Soviet Republics rather slowly, and as in China and Japan, silents were made all the way into the mid-1930s. Director Siko Palavandishvili had apprenticed with Kalatozov on Соль Сванетии (Salt for Svanetia, GSSR 1930), but was best known for his acting career in films such as Гвоздь в сапоге (The Nail in the Boot, GSSR 1931). Sadly for the viewing public, Zhuzhuna’s Dowry would be Palavandishvili’s first and only film as director, as he committed suicide soon after the release of the film. (His obituary in Kino was written by Eisenstein).

The festival catalogue accurately describes Zhuzhuna’s Dowry as “a comedy about horse-thieves, collective farms, and love”—and that order applies. Protagonist Varden (Giorgi Gabelashvili) may not be totally above-board, but he’s much more lovable scamp than unscrupulous villain, especially after an unwitting stint on the kolkhoz puts him on the road to redemption. A well-executed comedy that runs on gentle irony rather than slapstick, depicting rural Georgian life with familiarity and affection, Zhuzhuna’s Dowry was an unexpected delight.

– – –

It wasn’t a steady diet of silents, however—about a third of the 30-ish screenings I attended were talkies. As a big fan of both Yukio Mishima and Philip Glass, I’d been meaning to watch Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters (US 1985) for years. It’s a pretty unique take on the biopic, intercutting scenes from the infamous last day of Mishima’s life with imaginative realisations of several of his key works, as well as episodes from his childhood and adolescence. Cinematographer John Bailey was there to introduce the film, and his work on it was truly impressive, creating very distinct styles for each different section of the film.

Other highlights included Leave Her to Heaven (US 1945), part of the John Stahl programme: a Hollywood classic I’d never seen. A friend accurately described it as “a genre-breaker”: I enjoyed it thoroughly. I was also really glad to see La hora de los hornos part I: Neocolonialismo y violencia (The Hour of the Furnaces: Neocolonialism and violence, AR 1966-68); after watching this film, I really regretted not watching more of the Cinemalibero (revolutionary filmmaking) programme.

I caught a couple of the Chinese films, including 三毛流浪记 (The Winter of Three Hairs, 1949), which my friends and I picked purely based on the title. It’s an adaptation of the Sanmao (三毛) comic strip, which literally translates to Three Hairs, referring to the title character’s coiffure. These manhua roots showed in the film’s episodic structure, following Sanmao as he got into and out of all sort of scrapes—before communism arrived to save the day at the end of the film. The film’s assertion that the downtrodden masses would never go hungry again is, in retrospect, bleakly ironic.

Film Sanmao’s appearance mirrored that of his comics counterpart, complete with putty nose and those three hairs, which resembled small dreadlocks. A shot that stood out to me was when a character’s tattoo was animated, coming alive and scaring Sanmao—this comic-style visual trick didn’t recur, however.

Also interesting in terms of ideology was Марионетки (Marionnettes, USSR 1934), a political satire in which, via a series of shenanigans, a barber ends up king of Buffery, a nation in the grip of a power struggle between the fascists and the capitalists. Marionnettes was directed by Yakov Protazanov, of whom I can’t say that I’m a big fan: I’ve seen a bunch of his films, and while they’re decent and enjoyable, I generally find him rather workmanlike. He was the big box-office director of his time, working for Mezhrabpomfilm, the most commercial of the Soviet studios. I didn’t love Marionnettes as a work of cinema, or even comedy, but it’s interesting to see one of Protazanov’s sound-era films. Peter Bagrov of Gosfilmofond’s introduction to the film was excellent, providing a lot of context about Protazanov’s career and attitudes to his work, as well as describing how Marionnettes was repeatedly re-released and revived—even as late as the 1980s!

Finally, I should mention Laughing Anne (GB 1953), based on a Joseph Conrad short story. Not an distinguished film (it’s firmly a low-budget/B-picture), or even a particularly good one, but really quite enjoyable: I loved the transformation of the title character and the way that feminine laughter was a theme of the film, even being deployed strategically at the film’s climax. And who could forget the scene where Laughing Anne (Margaret Lockwood), adapting to life on the high seas, decides to remove her makeup by slathering butter (!) all over her face … only to reveal a new face containing exactly the same amount of makeup.

There was a strange visual artefact in the film, where the colour wavered slightly within shots. Laughing Anne was restored in 2017 by Paramount from YCM separation negatives, so one assumes that these colour fluctuations are due to the original laboratory processing (or perhaps even shooting), though that seems pretty odd for Technicolor. I haven’t been able to find out any more information on this matter—does anyone know?

– – –

Films and films and films …. but a huge part of the festival-going experience for me is the social aspect. And this was just wonderful! I stayed in an apartment with several of my close friends, and caught up with many others besides—Il cinema ritrovato is a great place to form connections, as well as renewing far-flung friendships! So thank you to all you lovely people for making it so much fun.

Reblogged this on Movies From The Silent Era.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on ithankyouarthur and commented:

An excellent summary of Bologna highlights, as you’d expect from S,P!

LikeLike

It was wonderful! I agree with everything you said. I’m so glad you said something about Christian Wahnschaffe because I literally don’t remember a thing about it except Connie’s clothes. Those blew me away.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yeah his clothing was definitely memorable!

What a great festival, so glad we got to spend a lot of it hanging out <3

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Il Cinema Ritrovato: Shiraz (India, 1928) – Thick thighs and bad guys

Pingback: Women and the Silent Screen: Elvira Notari |

How fortunate you are to have watched Francesca Bertini 💕 In Avarizia (1918)! I’ve watched the excellent early short Dream of An Autumn Sunset (1911) with Mary Cleo Tarlarini 🌸 and Antonietta Calderari 🌺 On YouTube. And I had the great pleasure of just watching Lyda Borelli 💕 just now in Carnevalesca (1918) with Italian/Spanish subtitles on YouTube! A powerful melodrama that begins with happiness, which eventually changes to palace intrigue. (No spoilers!).

LikeLike

Yes, it was a treat to see the clip of Avarizia! I think that clip is floating around online.

Cool that you mentioned Mary Cleo Tarlarini, I really like her.

And Carnevalesca is just wonderful. One of the best of all Italian silent films!

LikeLike